Via Streetsblog (which is via the National Safety Counci), motor vehicle-related fatalities increased for the first time in seven years in 2012--this number includes pedestrians and bicyclists killed by cars. The jump was pretty big, too, up 5% from 2011 to an estimated 36,200 total deaths. There's been a sense of cautious optimism as the number of fatalities has significantly declined over the past five years, tempered in part by worries that the improvement was temporary, due mainly to the recession's impact on peoples' travel and not a result of more permanent changes in road safety. Although we're still far short of the more than 43,000 deaths we saw in 2005, it looks like that caution may have been warranted.

One has to ask, though, why now? Why, despite the recession ending in Summer of 2009, did vehicle-related deaths continue to fall through 2011? If the recession were really responsible for most of the drop then it should have stabilized around the same time as unemployment, but that's not what we see.

For the beginnings of an answer to this problem, I looked to another report that was released recently: work by Michael Sivak at the University of Michigan showed that for the first time ever more women have driver's licenses than men (they had just 40% of total licenses fifty years ago). Men still drive more than women, accounting for 59% of total miles driven, but that too is an all-time low down from 76%. Men are, on average, relatively unsafe drivers; depending on the age group, they range from 30-100% more likely to be involved in fatal car crashes than their female counterparts, so having a smaller share of total driving being done by men seems like a win for road safety.

I bring this all up because, perhaps not coincidentally, men were also hit hardest by the recession--construction, manufacturing, etc. I wondered, what if the precipitous drop in traffic deaths wasn't just a general product of the recession? What if, in addition to the broadly immiserating effect of the recession, the decline in fatalities was also the result of a pronounced shift in the share of driving between men and women, driven by the disparate impact of the recession on the different genders? And what if that shift is reversing itself?

Unfortunately there's only detailed data up to 2010, but first we'll look at fatalities for just drivers and passengers, so we're excluding pedestrians, bicyclists, and the few people who die every year in bus crashes:

As you can see, although fatalities for all four categories have declined, in absolute terms the reduction in male driver deaths dwarfs those of the other groups. Of the ten thousand fewer deaths in 2010 compared to 2006, almost exactly half of those are male drivers. (The reduction in female driver deaths accounts for only fifteen percent of the total decline.) Interestingly, the percentage declines for passenger deaths were actually greater than that for drivers of either gender--those least likely to be responsible for the collision are benefiting most from the reduction in traffic fatalities. I'm using "being the driver" as a stand-in for "being at fault for the collision" because most people drive alone; it's not anywhere near a perfect model, but it should work decently well. If anyone has specific data that includes responsible party, gender, age, et cetera, please let me know!

What's responsible for this gender-specific decline though? To find out, I think it's instructive to look at unemployment rates over this same time period:

Both men and women were hit hard by the recession, but it clearly hit men harder, and we see the greatest declines in vehicle-related deaths in the midst of the worst of the job losses, in 2008-2009. As unemployment leveled out, so too did traffic deaths. But while men had more ground to make up, their recovery has also been notably faster. This is a result of the continued fiscal retrenchment at the state and local level, disproportionately harming women as teachers and other government workers continue to be laid off even as the private sector recovers at a modest pace. Hence, the "man-covery". Women didn't reach the same peak, but they've also barely recovered from that peak since 2010. It wasn't until the beginning of 2012 that the unemployment rates for men and women reached a rough parity: the same year that road deaths began to increase once again.

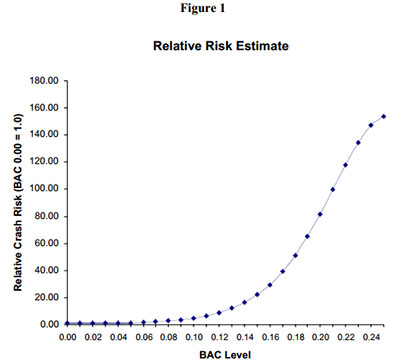

The fatality numbers are still significantly down from their high in 2005, but we also haven't fully recovered from the effects of the recession. For one, looking at the trajectory of the recovery for both genders, it may be possible that the unemployment rate among men actually drops below that of women as we get closer to a stable level of unemployment. Probably more importantly, the unemployment rate among men age 16-24 is still extremely high, and these are the most dangerous drivers on the road. As the recovery finally starts to take hold for these individuals and more of them start driving to work, it seems likely that the death toll will continue to climb.

Here's the vehicle fatality numbers broken down by age group:

Notice that even though the 16-20 and 21-24 age groups are smaller than the older groups (five and four year ranges rather than ten years), they each experienced declines over the past five years similar to the other groups. Combine them into a 16-24 age group and you end up with a decline of well over 3,000 deaths per year compared to 2005/2006, far more than any other similarly-sized age group. And unlike the other age groups, 16-24 year olds are still suffering immensely from the recession's effects--they haven't even begun to get back on the road, and yet in 2012 we've already seen a massive increase in road deaths. What will things look like in the coming years?

On the bright side, it really does appear to be the case that we're doing something right with new drivers--deaths among teenagers have been decreasing since 2003, long before the recession began. Less optimistically, almost every other age group's deaths had been increasing or holding steady up until 2007, and I strongly suspect that as the detailed data comes out for the past two years we'll see those declines for the 25-and-up age groups begin to rapidly reverse themselves. And it's going to be mostly men dying and causing the deaths of others.

This should be a wake-up call to any officials who might have been ready to take credit for improving safety on the nation's roads. It looked like, despite the recovery, vehicle-related deaths were staying relatively low. We're now beginning to see that this was just a self-serving fantasy. The continued improvement was more likely the result of men, and young men in particular, being disproportionately harmed by the recession--and the recovery is far from complete.

We need to do more to provide better, safer, more convenient options for travel and commuting that are inherently safer, not just more costly and therefore more difficult to keep using in the face of financial hardship. As the economy continues to recover and more men and women return to work, are they going to have any other choice but to get in their cars and roll the dice?