I’ve been asked by a few news outlets to comment on Councilmember Raman’s proposed Measure ULA transfer tax reforms. (You can read about the details of the proposal here.) Since I already wrote pretty lengthy responses for those, I figured I’d share them here for anyone else who wants to take a look. I’ve included cleaned up versions of the questions, in bold, with responses below.

Can you explain the benefits of Measure ULA? How about the negative consequences? There have been studies that found that Measure ULA has slowed the production of multifamily housing and other projects. What are you seeing in LA, and can that be attributed to the measure?

Measure ULA raises a lot of money to fund important housing programs including rent assistance and construction of housing for low-income people and people experiencing homelessness. The tax has raised just over $1 billion since it went into effect in April 2023. It’s a lot of money, and it’s permanently dedicated to addressing housing needs. I wrote a report in favor of progressive transfer tax reform in the city of LA way back in 2020, but unfortunately the initiative’s authors adopted almost none of my recommendations — and they weren’t brilliant ideas, by the way, just common-sense tax policy stuff.

Added to these benefits are some unintended (but predictable, and largely predicted) consequences. The relevant studies are:

Taxing Tomorrow — my analysis with coauthor Jason Ward of ULA’s impact on multifamily production and the cost of exempting projects from the tax for the first 15 years after construction

Unintended Consequences — Mike Manville and Mott Smith’s analysis of its impact on property tax revenues

Fiscal Externalities — another analysis of the impact on property tax revenues by researchers from Harvard, UC Irvine, UCSD, and U Mich

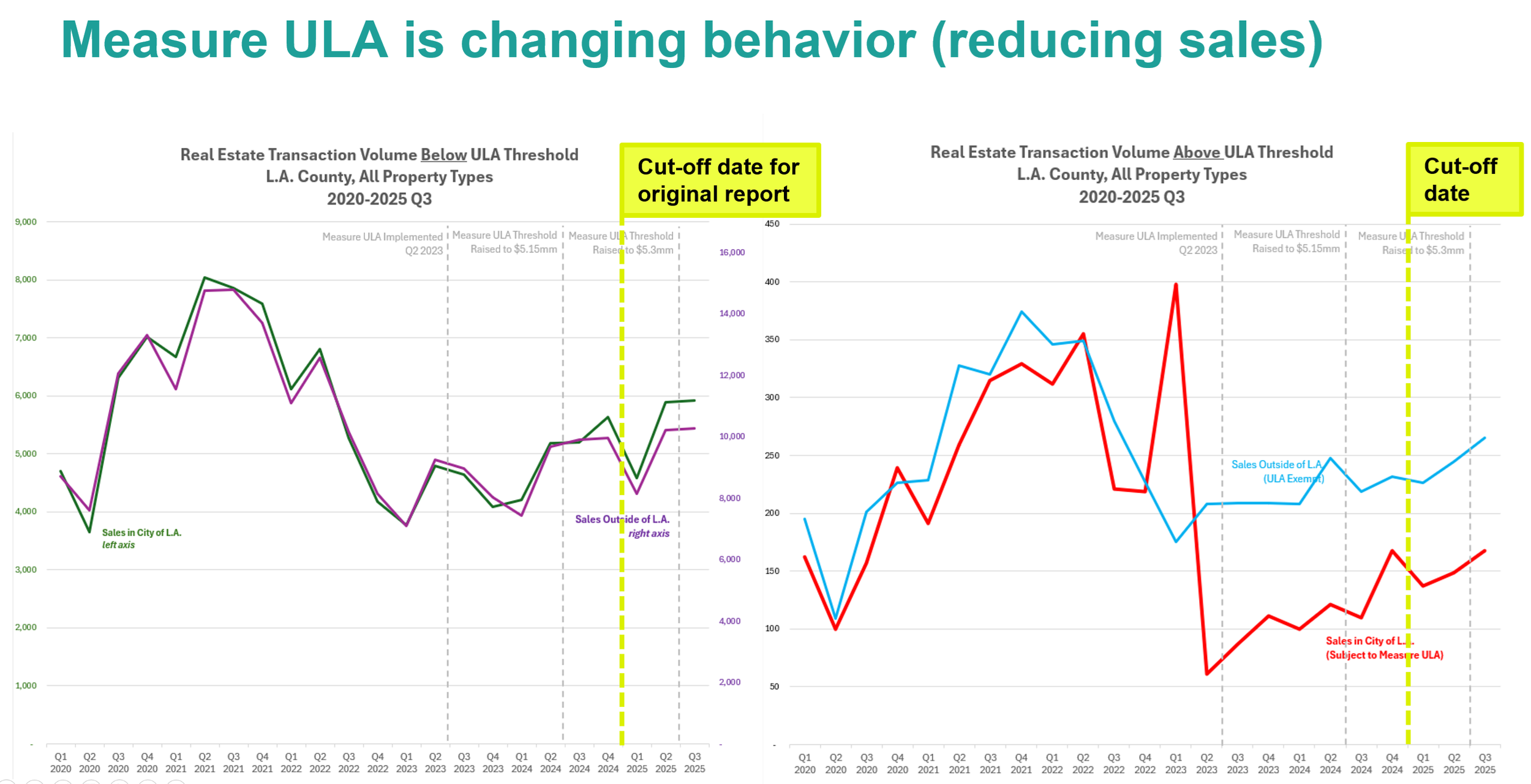

One consequence is that sales of properties over the ULA taxation threshold ($5 million initially, adjusted annually for inflation) have fallen dramatically in the city of Los Angeles. Sales of these properties have fallen much more than in other cities in LA County — about 50% more — whereas properties under $5 million have sold at similar levels before and after ULA was passed, inside and outside the city of LA. This is very strong evidence that ULA is responsible for the decline in sales of those higher-value properties. This is a problem, in part, because we rely on real estate transactions to produce a large share of property tax growth from year to year — thanks, Prop 13 — and property taxes fund city and county services and schools.

We've also seen a similar 50% decline in sales of properties that my coauthor Jason Ward and I identify as having the greatest potential for redevelopment. Again, this is relative to other cities in LA County, so it's not something that can be blamed on things like rising construction costs or interest rates, which everyone in the region experiences roughly equally. Some of the decline in housing permitting in Los Angeles is certainly caused by those things, but our research shows that ULA is responsible for a portion of it too. Based on permits issued within one year of these types of properties being sold, before and after ULA, we conservatively estimate the tax is reducing multifamily construction by around 1,900 units, including 170 for low-income households —homes that otherwise would have been built, and without subsidies.

Bottom line: Taxing privately-funded mixed-income apartments to subsidize publicly-funded apartments is lowering the supply of affordable housing in the city, and it's making housing more unaffordable for everyone by worsening the housing shortage. I think it’s fair to say that isn’t what voters had in mind when they approved the initiative. Measure ULA is known as the "mansion tax," but ironically mansions are the only housing type we're building significantly more of — permits for single-family houses are up roughly 40% since 2022. Multifamily permitting is down about 40%.

Side note: The campaign behind Measure ULA has been forcefully and caustically opposed to any reforms, and they’ve characterized Councilmember Raman as attempting “to line the pockets of billionaires and developers.” Aside from it being a truly unbelievable accusation to lob at one of the council’s stalwart DSA-aligned members, it’s telling that there’s so much focus on making those bad guys pay when what really matters is who’s hurt when we build less housing. Hint: it ain’t the billionaires.

Some housing advocates, like United to House LA , have said studies showing that construction slowed down due to ULA are “faulty” or “invalid.” They argue that the construction is on the upswing as more time passes and more developers accept the measure. Can you address these concerns? What is the data telling us about the measure?

No social science research is perfect, but they've failed to back up their critiques with evidence, and they've repeatedly made false claims exaggerating the benefits of Measure ULA. That's unfortunate because I think the tax's benefits are strong enough when presented honestly. You can see our response to their claims, including a rebuttal to their statements about ULA's benefits here. This quote summarizes the first half of the report:

“Any study can be improved, and as more data become available we plan to augment our analyses of Measure ULA ... But the fact that more work could be done isn’t reason to discount the work that has been done already. The evidence presented in “Taxing Tomorrow” is strong, methodologically transparent, and entirely consistent with a large body of empirical research (virtually every study of “cliff-style” transfer taxes has findings similar to those of the Lewis Center’s work). The argument we advance is also consistent with basic economic theory and common sense ...

The coalition has argued that this isn’t the case, and that our work is flawed. It has done so by saying we only examine one quarter of data before Measure ULA (we actually measure 11); that our pre- and post-time periods aren’t symmetric (that doesn’t matter); that we don’t control for other factors (we do); that ULA transactions are rapidly trending up (they are, but very slowly, and aren’t currently on track to converge); and that development has increased in Santa Monica and San Francisco (it hasn’t).”

The analysis by Jason and I used data through March 2025, and the one by Mike and Mott went through December 2024. We recently re-ran the estimates of sales volume using data through September 2025 and we found that the 50% reduction has persisted, despite earlier claims that the gap was rapidly closing. Here are some figures with updated data that shows where the original study cut off:

As for the claims that production is recovering — their data were cherry-picked, and quite egregiously so. I explain how here, but if you want the quick summary, here’s another pull-quote:

“First, the statement that permits are up 60% in the 3rd quarter. This is is true but misleading. Why? Because up to that date, Q3 2024 was the worst quarter for housing construction permits since before 2020 ...

So yes, if you arbitrarily choose the worst quarter of production in 4+ years (probably 8+ years) as your baseline, you’re likely to show improvement in later quarters ...

The group also says permits rose quarter-over-quarter through 2025. Again, true but misleading, and for a similar reason. This chart shows quarterly permitting through Q3 2025, with Q1 2025 circled. This is their baseline for this claim — the worst quarter in 5 years ...

Maybe production is recovering, but there’s not much data to support that conclusion yet — unless you use it dishonestly. If we look at annual figures, which smooth out some of the quarterly variability, 2025 looks about as bad as 2024, which itself was historically bad.”

What do you think of Raman's proposal to carve exemptions and tweak the measure to allow more traditional lenders to support ULA-supported housing projects? Do you anticipate these proposed changes to make a tangible difference?

I voted for Measure ULA and urged others to do the same, but the unintended consequences exceeded my expectations. But as I've said many times, the worst impacts are easy to fix and not very costly — surprisingly so, if I’m being honest.

My analysis with Jason showed that only 6-8% of revenues come from multifamily buildings 15 years old or less, and exempting these projects — what we recommended in our report, and exactly what Councilmember Raman's proposal would do — is likely to bring back a lot of the homes made infeasible by ULA. So yeah, I’m for it.

It's a small price to pay, considering we can barely fund 100 units of subsidized housing with 6% of ULA revenue. And if we don't restore private homebuilding in the city, there'll be even fewer new projects to tax in the future. 6% this year, and by 2030, who knows? 4%? 2%? Well, at least we made the billionaires pay.

The other changes, including making it easier for lenders to issue debt to ULA-funded projects, are also important and very welcome.