Warning: This is a very long post that gets deep into the weeds on the proposed DTLA 2040 Community Plan update. Seriously, it's like 9,000 words. It's intended for those who have already read the much shorter summary of the plan's key features (based on the limited information available from City Planning at this time), the major flaws or problems as I envision them, and a number of recommendations for improving it. You can find that summary here. After reading it, if you want to learn more about the details of my counter-proposal and my arguments for why we should demand more from the Planning department, this is the post for you.

Over the next 6 to 12 months, the shape and direction of downtown LA's next 20 years are being decided.

As part of a program called DTLA 2040, LA's Department of City Planning is in the midst of updating the two downtown LA community plans. They began their initial public outreach in October with a week-long "open studio" event where members of the community were invited to come by, learn about the proposed changes, and provide their own input and vision for the future of the approximately 6 square mile neighborhood.

Between the approval of Measures M, HHH, and A, and the conversations about LA's future at the heart of Prop JJJ and the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative, this work couldn't be coming at a better time. And with the City looking to finalize their plans over the coming months and implement them by early 2018, we need all hands on deck to ensure that we get a community plan that appropriately reflects our status as the vanguard of LA's future.

The two Community Plan Areas being updated through the DTLA 2040 effort, Central City and Central City North.

As things stand, the Central City and Central City North plans are based on the growth projections of the Southern California Association of Governments: By 2040, they're expecting 55,000 new jobs, 70,000 new households, and 125,000 new residents. That might sound like a lot, and for any other sliver of the city (these two community plans represent just over 1% of LA's geographical area), it would be. But I've written in the past how growth projections and housing allocations are basically bunk, and I think we'd be especially foolish to plan according to those projections here in downtown LA.

Downtown will grow by this much if we plan for it, sure—but is this all we want?

Theory of Change: The More We Grow, The More We Control and the More We Get

My reasons for wanting more are simple: The more we allow to be built, the more value is created on downtown parcels. The more value we create on downtown parcels, the more we can recapture in the form of affordable housing, open space, transportation improvements, and other community priorities. I want to see us go big on all of those investments, and the money to fund them won't be forthcoming from outside sources; we need to create the necessary resources here at home. I also believe that there's nowhere in Los Angeles where redevelopment would be more welcome and less impactful than in downtown LA, and that we can serve as a model for the future of our city—for what Christopher Hawthorne calls "The Third Los Angeles."

Here's a simplistic example to illustrate what I mean by creating value and "getting more":

Say I own a parking lot, but the zoning code says I can only build a 1-story building on it. Because I can't do much with it, it's not worth a whole lot. Now say the city changes the zoning code and allows me to build up to 3 stories. That plot of land is now without question worth more than it was before: if before I could build 10 housing units, now I can build 30, give or take. That's such a good deal for me that I'd probably even be willing to set aside 5 of those units for low income households in exchange for the right to build all 30; the 25 remaining market-rate units more than make up for it. And just like that, we've created value for the property owner (increasing development capacity from 10 units to 30) and then re-captured much of it it on behalf of the community (in the form of 5 affordable homes).

Now imagine if instead of going from one-story to three, we went from three stories to 10, or 12, or 14. Or if we allowed housing or office space to be built where nothing except warehouses can currently be built. Not only will have you created the opportunity to build much more housing—which we desperately need at any income level—you've also increased the value of many of these parcels by 3x, 4x, 5x. Multiply that by over 1,000 acres of underutilized downtown land, and you've got billions of dollars to reinvest in priorities of local and regional significance.

To be clear, choosing to redevelop downtown—and do so in a transformative way—is not the same as choosing to destroy the various districts and communities that make this a special place. On the contrary, the Toy District, Fashion District, Flower District, and others will only survive with a community plan that accommodates redevelopment and links that added value to protections for existing residents and businesses.

The proposed redevelopment of the Southern California Flower Market is a great example of how redevelopment can be used as a tool to preserve a district's distinctive character: If approved, the project would not only preserve and upgrade the Flower Market and allow it to stay on site, it would also add 320 new homes, 10 percent of them for low-income households. Just as I'm proposing for the community plan update, the owners of the Flower Market are adding value by asking to build more, and returning much of that value in the form of business preservation and renovation and affordable housing. We need a plan that proactively encourages similar activities throughout downtown rather than relying only upon the good intentions of each and every property owner.

The proposed Southern California Flower Market redevelopment would "call for the demolition of one building to construct a 15-story residential tower with around 320 units, 10% of them below market rate," and would preserve and renovate the Flower Market itself. Source: LA Times.

Shortcomings of the DTLA 2040 Plan

In my view, the proposed community plan update focuses too much on the preservation of the downtown aesthetic, and too little on increasing affordability and access to opportunity. It's form over function: the appearance of stability, using the built environment as a proxy, over actual stability—and enriched lives—for the residents and employees of the community. Under this plan, the Arts District will continue to look like the Arts District, except maybe a bit bigger. The Industrial District will stay industrial, with no housing allowed, and freight traffic continuing to make our streets unpleasant places to walk and bike. The Fashion District will grow, but not by too much.

Assuming that all 70,000 housing units and 55,000 jobs show up by 2040, they'll look very similar to what we've seen in the western side of downtown over the past 10-15 years: heavily skewed toward market-rate/luxury housing; a limited supply of affordable housing; a few small new parks like Spring Street Park and the new Arts District Park; creative office and high-end retail replacing (rather than complementing) small-scale entrepreneurs and non-tech start-ups; and buildings with almost as much space dedicated to parking as to housing—and the boring architectural features and heavy traffic that accompany that kind of car-oriented design. It's not a horrible outcome, necessarily, but it's not half of what it could be.

If I can guess at the reason the plans are being pitched this way, it's that bold plans are often met with fierce resistance in other parts of LA. Hell, even mediocre plans are met with fierce resistance. People in most of this city hate change. We're being sold something that the Planning Department feels is minimally disruptive, and therefore more likely to get through an approval process that's never anything less than challenging. So I understand why they're coming to us with a proposal like this. Anywhere else in the city, 70,000 new households within just 5 or 6 square miles would be met with pitchforks.

But I think we're being underestimated.

I think downtown is different from the rest of Los Angeles, and that if you show us something truly visionary, we're ready to get behind it. Maybe I've got my head too high up in the clouds, but I really believe that.

Hopefully you're with me up to this point. Now we have to answer the difficult questions of how do we actually get something better... and what, exactly, does "better" even look like?

Downtown LA—particularly its west side—is one of the main economic engines for our region, and is increasingly important as a residential and cultural center as well. Why shouldn't we want the rest of downtown to follow suit, especially when doing so gives us the resources to solve many of the city's biggest challenges?

What Should Downtown Prioritize?

Planning is ultimately about trade-offs: balancing the needs and desires of different community stakeholders with the needs, desires, and resources of the rest of the city. One of the most important messages I try to communicate in my writing is that while we can absolutely find win-win solutions to many of the challenges before us, we can't have it all. Our neighborhoods can't stay exactly the same and somehow function dramatically better, with more affordable housing, open space, and walkable streets. We can't just stick our heads in the sand and hope things get better, and we can't demand change if we're not willing to make changes ourselves.

Before the DTLA 2040 community plan update is complete, we need to ask ourselves what we value and what we want to achieve, then we need to grapple with what trade-offs we're willing to make to get there.

As we've seen in other neighborhoods across the city, preserving a community's physical form isn't enough to prevent gentrification and displacement—just look at places like Highland Park and Silver Lake. They haven't grown "up" all that much, but that hasn't stopped property owners from responding to increased demand by raising rents when tenants move out (or evicting them to force the issue), renovating their units to appeal to higher-income residents, and flipping the homes that are already there.

Whether or not redevelopment takes place, the value of these communities is going up, just as it is in downtown. By freezing the built environment in place, we simply ensure that 100 percent of that added value goes to the existing property owners. If instead we choose to value the people within the community above the buildings that happen to be located there, and then plan in a way that reflects those values, we can benefit the whole community rather than only those who own the buildings.

Below are the five areas where I believe we should focus our efforts, along with a comparison of what DTLA 2040 currently promises us versus what I think we can achieve.

Affordable and Market-Rate Housing

Housing is the linchpin of this entire plan, so I'm going to spend extra time discussing it.

But here's the jist of it: We need to a build a whole lot of housing in downtown. Wayyyyy more than 70,000 units. As long as our city is stuck in the midst of a housing shortage, vacancy rates will stay low and rents will keep going up. Every day we delay brings us one step closer to becoming San Francisco. According to the Legislative Analysts Office, LA County needed to build an additional 35,000 housing units per year over the past 30 years to keep prices from rising faster than the rest of the county. We're not going to catch up on a 1,000,000-unit housing shortfall anytime soon, but we're shooting ourselves in the foot by aiming so low in the most development-friendly neighborhood in all of Los Angeles. If anyone's going to lead the way and take bold action, it's going to be downtown.

Figure from the 2015 Legislative Analysts Office report, "California's High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences."

A large amount of that housing should be affordable to low and moderate income households, as well as the formerly homeless, and the very good news for downtown is that more market-rate housing means we can subsidize more affordable housing. They can and should go hand in hand. Given the amount of investment in our Metro Rail network that's centered on downtown, we have a responsibility to create as many homes and jobs as possible that are accessible by transit.

What we'll get from DTLA 2040:

Because the changes proposed by DTLA 2040 are relatively modest, there's not much we can ask for from new development in terms of affordable housing, tenant protections, etc. If we manage a 20 percent affordable housing set-aside (an ambitious goal, all things considered), we'll end up with about 14,000 homes affordable to low/moderate-income households, and 56,000 market-rate units by 2040. That's nothing to sneeze at, but over a 20+ year period it won't put a dent in our housing shortage and it's far less than we can accommodate, and not enough to truly "fill in" the area in a way that creates a contiguous, cohesive downtown from the 10 to Chinatown, and from the 110 to the LA River. Some areas, such as the industrial area in southeast downtown, won't have any housing at all. They'll basically remain as they are indefinitely.

This preservation doesn't come cheap: it comes at the expense of tens of thousands of affordable and market-rate homes that could be built directly adjacent to Metro's future West Santa Ana Branch rail line, along with many thousands of jobs to replace the much smaller number of warehouse and manufacturing jobs that would be displaced. Whether we preserve downtown's industrial zones or not, automation and globalization mean manufacturing jobs are on their way out, and they're not coming back. Despite a modest recovery since the recession, total manufacturing jobs are down to 12 million from a 1998 peak of 17.5 million. We can wait for them to leave downtown one employee at a time, and leave those workers to deal with the consequences unassisted—or we can respond proactively, make far better use of their land and capture the value inherent in such high-demand locations, and use a portion of the funds we raise to relocate and retrain those in need of support.

What we should be asking for:

SCAG and the City want to plan for 70,000 new households; I say we plan for at least 200,000. That means zoning for at least 300,000, since many property owners will hold onto their parcels regardless of the incentives to redevelop (just look at the parking lots and one- and two-story buildings still littered throughout the Historic Core and South Park). Will all 200,000+ units be built by 2040? Almost certainly not. But you don't get what you don't ask for.

Done right, more housing is not something downtown needs to "put up with" or "accept." It strengthens us, allowing more people to live close to where they work and play, reduce their dependence on driving, support local businesses and encourage more of them to locate in transit-friendly downtown, create new amenities like open space and transportation improvements (to be discussed more below), and, frankly, to demonstrate to the rest of the LA region what they're missing out on. If Beverly Hills and Santa Monica don't want new housing, we'll take it—and we'll turn that investment into something that creates a more equitable and affordable city while also enriching our own lives in the process. It also strengthens us as a truly diverse community, allowing us to create anywhere between 30,000 and 50,000 units of affordable housing (15 to 25 percent of the total).

At 54,000 people per square mile, Paris is the most dense city in Europe. Many neighborhoods in Paris house considerably more people per square mile. By comparison, Koreatown is LA's most dense neighborhood, at roughly 40,000 people per square mile. When done right, density is not something to be afraid of. We just need to make sure we're asking for the right things.

What we absolutely don't want is to underestimate the demand for housing and perpetuate the broken planning system we rely upon today. Right now LA is home to about 4 million residents, and zoned for just a few hundred thousand more. This not only creates an artificial scarcity that drives up the price of the land available for development or redevelopment, it also leads to problems where demand is misaligned with development capacity in specific markets, and projects in those areas depend on "spot zoning" and ad hoc political negotiations to get built. The reliance upon spot zoning, and the appearance of backroom dealing and corruption that accompanies it (regardless of whether actual corruption is present), is the main rallying cry of destructive proposals like the Neighborhood Integrity Initiative.

Chart illustrating LA's self-inflicted decline housing capacity over the past 50 years, from the dissertation of former UCLA Ph.D. student Greg Morrow.

Displacement Mitigation and Tenant Protection

One of the great strengths of downtown redevelopment is that relatively few people live in places like the Fashion District and the industrial zones of downtown, so fewer people are displaced when new developments go up. But some people will still be displaced, and we need to do everything we can to ensure that they're able to stay in the community and ultimately benefit from the local reinvestment as much as anyone else. This is important not just because it's the right thing to do, but because the passage of a bold 2040 plan will be dependent on buy-in from the whole downtown community: everyone needs to see how this plan will benefit them, which means, of course, that everyone needs to be able to stay.

What we'll get from DTLA 2040:

We've already covered the good news here: up to about 14,000 units of affordable housing. The bad news is that those affordable units are very unlikely to protect current downtown residents or do anything about displacement. Usually, affordable housing units are filled up by a lottery, so being a member of the community doesn't typically give you any advantage; it's luck of the draw, and of course only low-income (and sometimes moderate-income) households are eligible. If you happen to be displaced by redevelopment and you're not a low-income resident, well, you're just out of luck entirely. Even if it were a priority to re-house displaced tenants, regardless of income, DTLA 2040 just doesn't create enough value to be able to fund those kinds of efforts. Downtown has a great track record of development without displacement, but there will still be some casualties under this plan, unfortunately.

What we should be asking for:

As I've written about before, we need to prioritize relocation of displaced tenants to homes of similar (or better) quality, at a similar (or lesser) price, in the same (or very nearby) neighborhood. For too long, we've asked existing residents to make huge sacrifices on behalf of future residents, with basically nothing offered in return. We can't freeze our cities in time, so if this were a necessary evil, it might be worth the cost. But it's not necessary.

By adding density and recapturing its value at the time of construction, we can easily afford to create new affordable housing and take care of existing residents. The simple solution is to set-aside a relatively small portion of the value capture revenues and use them to temporarily re-house displaced resident—or permanently rehouse them, possibly through the non-profit acquisition of existing housing in the area, if that's their choice.

For those that choose temporary relocation, they should have first dibs on the new units built in place for their former homes, and they should pay no more than 35 percent of their income on rent, no matter how much they make. For many tenants this would be a huge improvement in their lives, with better housing as well as less of their income spent on rent each month. And why shouldn't they be eligible for something like that? Displacement and temporary re-housing is a huge burden on people's lives, and they're bearing perhaps the greatest burden of redevelopment. And in a place like downtown, where more than 8,000 units were built in the Central City and Central City North between 2010 and 2015, and only 35 multifamily units were demolished, this is something we can absolutely afford.

Again, this is an opportunity to set an example for the rest of the city, and cities around the country. We shouldn't let it go to waste.

A photo from the anti-Build Better LA press conference held on July 19th, 2016 at the Yucca-Argyle apartments, where 40 rent-stabilized units are set to be replaced by 39 low income and 152 market-rate units.

Parks and Open Space

There's a huge shortage of parks and open space in Los Angeles, and there are few places where that shortage is felt more acutely than in downtown. We need more small parks and parklets, yes, but what we really need is one or two more full-size open spaces on the scale of Grand Park, 20 acres or more. If downtown builds up enough elsewhere, we can afford to reserve whole blocks of land for conversion to parks.

What we'll get from DTLA 2040:

At this point, it's not really clear. We can definitely count on more medium-sized spaces like Spring Street and Arts District Park, funded in part by Quimby fees and revenues from the recently-passed Measure A. There'll probably be plenty of small-ish pocket parks, parklets, and the like. With plans for over 100,000 new residents, we'll definitely need them. New developments will also continue to be encouraged to provide their own open space, like that included as part of Mack Urban's 12th and Grand mixed-use development.

Parklets are great additions to the urban fabric of a neighborhood, but they can't take the place of real, full-sized parks. Photo from DTLA Rising by Brigham Yen.

What we should be asking for:

What we should be asking for, and what we genuinely need, is at least one more park on the scale of Grand Park. We need something that is at least 20 acres, something that stands out as a destination and gives residents a place to walk and jog without crossing a bunch of dangerous intersections, meet with friends after work, relax on a sunny weekend afternoon, and provides a refuge of sorts within the busy downtown environment. The park should also be contiguous. One of Grand Park's greatest weaknesses is how it's broken into narrow slices by the roads passing through it—and anyone who's walked from one end of the park to the other knows that car traffic is heavily emphasized over the convenience of pedestrians and park visitors. We shouldn't make the same mistakes with future parks.

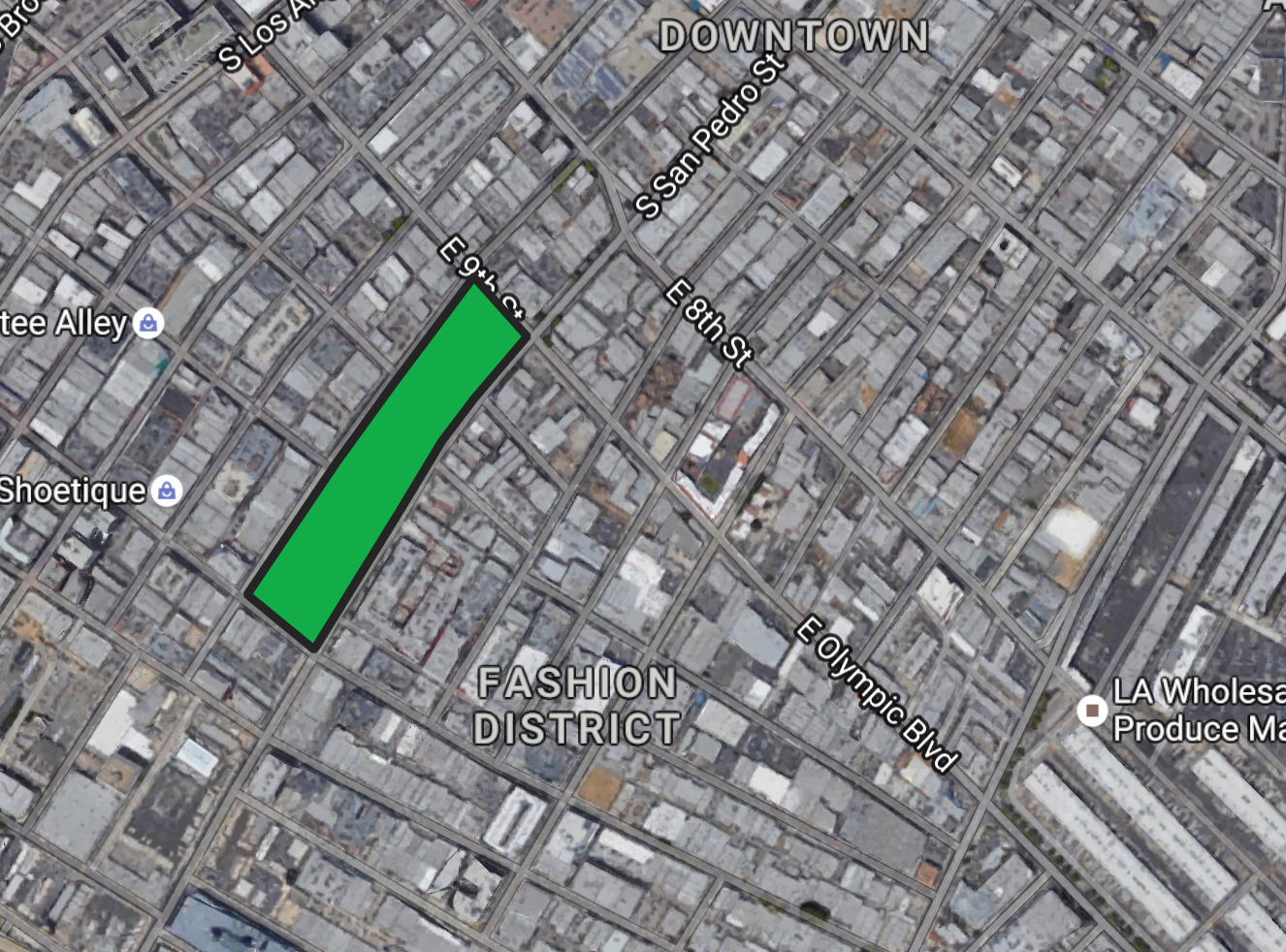

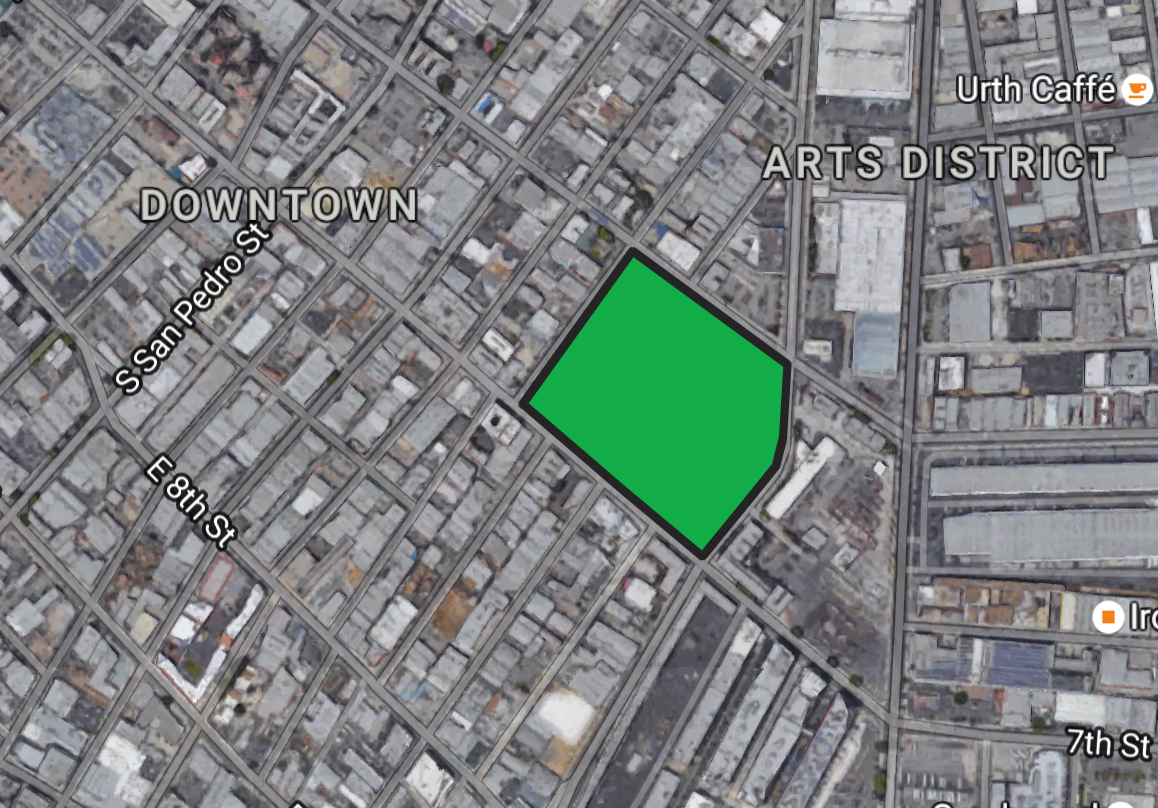

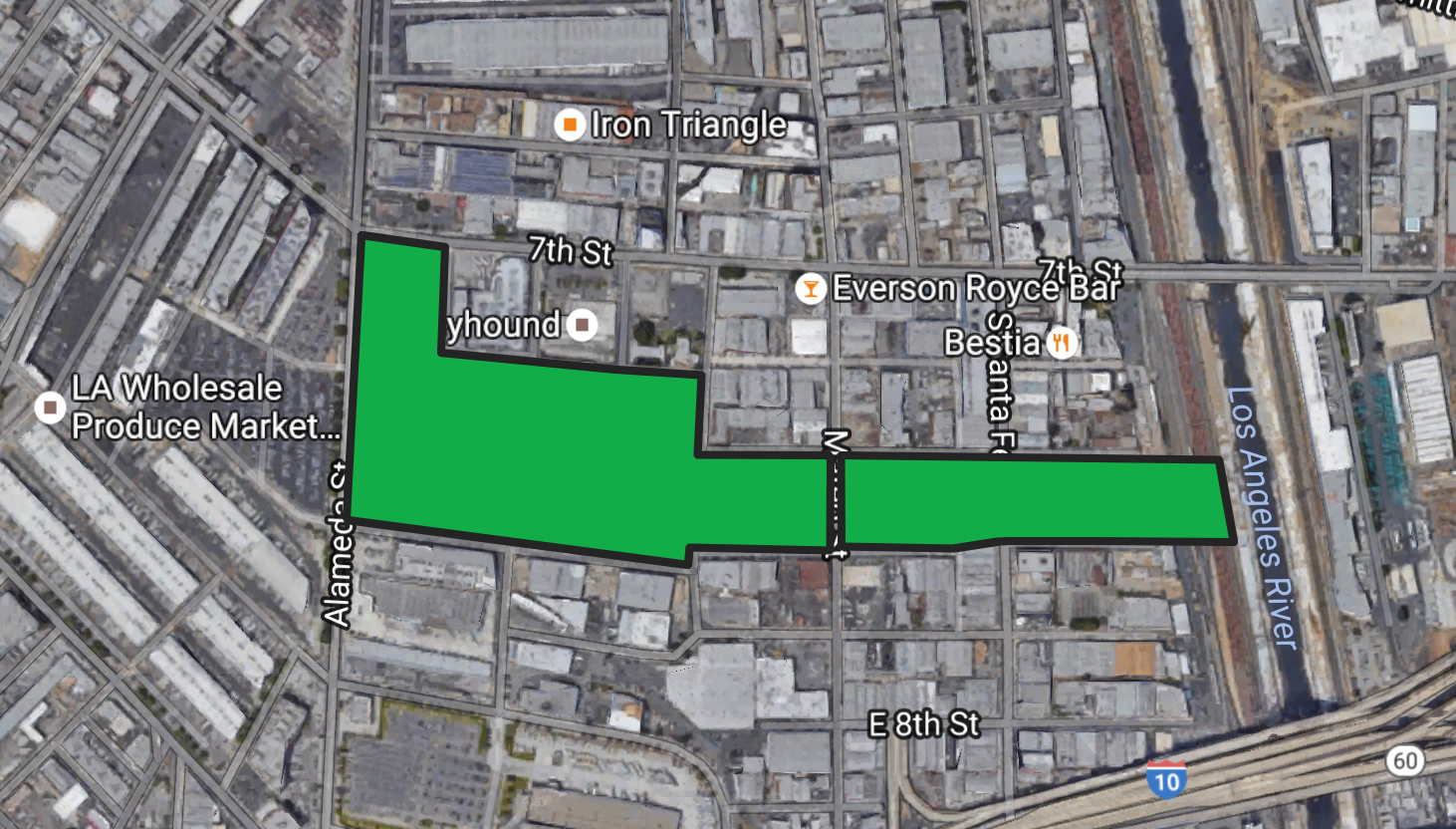

Below are a few examples of where parks could be located. Don't read too much into the locations; this is just intended to help visualize the scale.

As with value capture, this only works if you go big on redevelopment. Purchasing 20 acres of land, even at the low price of $100 per square foot, would cost $87 million. And that's before you actually spend any money designing and building the park. (I don't know what the per-square-foot value of land in the less desirable parts of the Fashion District or Industrial District is; this is almost certainly a low-ball estimate given the $500+ psf cost of land in the higher-demand parts of downtown.) Whatever the cost, a large park should be a priority in the south or east part of downtown even if only 70,000 households were added over the next 20 years. With 200,000+ units and the commercial development that would accompany it, a large park becomes even more essential—and, more importantly, it raises the funds to actually make such a park financially feasible.

The southern/central park of downtown needs its own version of the LA State Historic Park (Cornfields). The only way we're gonna get it is by building enough housing to raise the necessary funds and creating the demand necessary to support it.

Transportation

If everyone who moves into all of these new units drives frequently—even if we only ever built the 70,000 new homes in the City's proposal—downtown LA would be a gridlocked disaster. It already is a gridlocked disaster at various times and locations throughout the day. To accommodate a lot more people, the future of downtown development needs to be a lot less car-oriented, which means we need effective alternatives to driving, and we need them soon. We've already got a good rail network on the western end of downtown, and the future West Santa Ana Branch will connect eastern DTLA to Union Station (thanks Measure M!), but we also need to connect the areas in between.

What we'll get from DTLA 2040:

If development pressures increase in the Fashion District, Skid Row, and Industrial/Warehouse District to the southeast and there are no good transit options available, these neighborhoods will continue to put cars first. That means significantly less housing at significantly higher prices (a single structured parking space can raise rents on a unit by $200 to $400 a month), and a much less walkable, attractive neighborhood. To some extent, the DTLA 2040 plan ensures this. It's not transformative enough to promise anything but more of the same: new and improved sidewalks in some places, bike lanes in others, maybe even some new DASH routes over time. More of the same wouldn't be a disaster, as I've said above But it's so much less than we deserve, and nowhere near what downtown could achieve.

As an urban planner, and even just as a taxpayer, one of the most distasteful parts of the current DTLA 2040 proposal is how we treat the southeast corner of downtown. This is an area that's currently full of low-density industrial uses, warehouses, and some housing. Right now it has the worst transit access out of both Community Plan Areas. Before too long, though, it will be home to the West Santa Ana Branch light rail line, which will connect the Gateway Cities to Union Station through eastern downtown LA. To leave this area industrial, and to maintain the housing ban, is a total waste of this investment. Especially in an area that is so underutilized and full of so much potential—and in contrast to other rail line stations that are in the midst of "mature" neighborhoods—it seems a travesty to preserve these low-intensity uses. It could be a transit village comparable to any other in the county, or even the nation, and we should demand that it become exactly that.

What we should be asking for:

Five of LA's seven existing rail lines meet in downtown LA, and by 2020 their reach will be extended by the streetcar circulator. A bit after that, the West Santa Ana corridor will be running down the east end of DTLA. Given this abundance of rail resources, downtown should be a transit mecca—a place where most people get here by transit, and everyone gets around here by transit. Traveling from any corner of downtown to any other corner should be quick, convenient, and traffic-free. We can achieve that goal only if we build densely enough to support frequent transit service and dedicated transit lanes throughout the neighborhood.

I'll admit to a bit of bias since my day job involves working on the LA Streetcar, but for my druthers I think that an interlocking web of streetcar lines—filling all the interstitial spaces between Metro's light rail network and extending into adjacent neighborhoods—is the ideal solution. Streetcars also have the added benefit of promoting economic development, and would encourage developers to make the highest and best use of their newly-realized zoning capacity. If we're going to fill in our community with hundreds of thousands of new residents, a major investment in transit will be necessary to get them around: cars, or even buses under most configurations, just won't cut it. Bus rapid transit (BRT) could also work as a potential solution, but only if it lived up to the name, and wasn't just built as a watered down version of what's really needed.

Metro Rail (colored lines) will frame downtown on all sides: Red, Purple, Blue, and Expo Lines on the west and north; Blue on the south, and the future West Santa Ana branch line on the east. What services will be available to connect the areas in between and beyond?

Streetcar or high-quality BRT would be needed to connect residents and workers to the broader Metro rail network, but people also a need safe, comfortable means of getting to the bus or streetcar stop. This is where investments in new streetscapes, sidewalks and protected bike lanes take center stage. We're going to need a transportation network that is world-class from top to bottom, and with Measure R and M we're already well on our way with the major rail assets that connect cities to other cities, and neighborhoods to other neighborhoods. With enough new housing and the revenues that accompany it, downtown can fill in the gaps at the local level, too.

Business Retention and Employee Retraining

When we talk about gentrification and displacement, we're usually talking about impacts on residents, but there are hundreds and possibly thousands of small businesses throughout central, south, and southeast downtown that would be affected by redevelopment. There's value in allowing businesses to succeed or fail on their own merits, but we should also be sensitive to the fact that there are thousands of livelihoods tied up in the these downtown districts. We should strive to preserve the industries that have organically concentrated here even as the urban form and design of these neighborhoods changes.

What we'll get from DTLA 2040:

In the proposed "Industrial Preserve" area of the community plan update, no housing would be allowed at all. This is intended to protect vulnerable warehouse and manufacturing jobs, because housing development is so much more valuable than commercial or industrial development, so anywhere housing is allowed will typically see almost nothing else built. I understand the motivation here, but I think it's misguided.

Automation has taken up a bigger and bigger share of manufacturing and warehouse work over the years, and there's no reason to think this trend won't continue. By preserving the industrial zoning in southeast downtown we may end up helping a few hundred or thousand workers keep their jobs a little longer, but they will nonetheless continue to trickle out as their work is replaced by robots, bit by bit. We'll have preserved 1,000 acres of land in the most valuable and transit-accessible location in the region, only to see it serving a smaller and smaller number of jobs and zero residents. And because we're relying on a stop-gap measure intended only to delay the inevitable, rather than planning proactively, we won't be able to ensure a smooth transition for these workers when they eventually do move on.

What we should be asking for:

You may disagree with me on this, but I would argue that housing costs, not jobs, are actually the greatest obstacle to LA's long-term success and the ability of its residents to continue to thrive. Over the last 10 years we've lost over 7 percent of our Millennial population, the third-greatest loss in the entire country. We cannot, cannot, can not continue on this trajectory if we want to avoid San Francisco's monoculture fate, and downtown offers us the greatest opportunity to chart a different course. To emphasize the choice before us, I'll illustrate it by by its extremes: we need to choose between 1) the short-term stability of a few thousand jobs, or 2) the long-term affordability of a city in which 4 million people now live, and millions more will flock to in the coming decades.

For the work already being done in downtown, I have a few general thoughts on the approach we should take. One is to tone it down on the preservation of existing buildings and "character." Character is the word people use when they want to justify opposing change, no matter the cost to others, and I kind of hate to see the Planning department use it so indiscriminately. Speaking purely to the physical character of the buildings in much of southern and eastern downtown, this is generally not world-class architecture worthy of preserving. If these neighborhoods look different than they used to, that's probably an okay thing in most cases. I think Seattle has taken a reasonable compromise approach on this issue, retaining facades in historic districts like Capitol Hill's old Auto Row, while still allowing for redevelopment that adds desperately-needed housing, new greenery, and streetscape investments.

A new building in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood, where the facade was maintained and 5 stories of housing were built above it. The pre-redevelopment business, a bar named Bill's Off Broadway, returned to its location on the ground floor when development was complete.

Another example of a Seattle redevelopment with a retained historic facade, 3 blocks down the street from Bill's Off Broadway.

Using this approach in the industrial district, it's possible that some existing uses—especially those that serve nearby businesses in the Fashion District, Flower Dsitrict, and elsewhere—could be retained. A forward-looking plan might also consider closing off one of the smaller east-west streets to normal traffic and allowing only transit, light freight, pick-up/drop-off, and pedestrian use. In cases where existing businesses are entirely incompatible with a walkable community, value capture funds could be set aside to assist with relocation and/or worker retraining. The upside to residential land being so much more valuable than commercial land is that, by rezoning for housing, we can create the value needed to actually mitigate the impacts of redevelopment.

For non-industrial areas like the Fashion District we'll need a different approach. Here, we should explore ways for existing businesses to stay in the area. While displacement will be unavoidable during redevelopment itself, only a small share of buildings will be under construction at any time and so it should be possible for businesses to relocate to nearby spaces. The greater challenge will be designing future buildings in such a way that the existing tenants can return. Whether that should be mandated is a conversation worth having; one way or another, we need to find a way to ensure that existing residents and businesses can benefit from redevelopment as much as those able to call the area home in future years.

When possible, and where the businesses find it desirable, allowances should be made so that legacy businesses can return to their old location at similar lease rates, at least for a period of 5 to 15 years (for example). Again, this is only possible because of the value inherent in upzoning.

Creating Value to Fund Our Priorities

Obviously that's a big, expensive list of priorities. In principle, they're things I think just about anyone would support. Maybe your list looks different, and that's fine—if you put a dozen people in a room you'll probably end up with a dozen different plans. Whatever your personal priorities, and whatever priorities the downtown plan ultimately decides on, what really matters is that they won't come free and they won't happen spontaneously. We don't get what we don't plan for.

Once our priorities are set, however they're set, we need to figure out how to turn them into reality. Looking at the Expo Corridor Transit Neighborhood Plan (TNP) is a good place to start.

In the Expo Corridor TNP, which proposes to upzone/rezone the areas within a quarter-mile of Expo Line stations, value capture works as follows: To build beyond existing (pre-TNP) zoning, you must accrue a debt of "points," as seen in the table below. The bigger you build beyond pre-TNP zoning, the more points you accrue, and the more amenities you must provide. Amenities include things like publicly-accessible open space and streetscape improvements, among other things. Each of these amenities has a specific point value—for example, building out the entire streetscape along Bundy Drive between Missouri Ave and Expo Blvd would net you 30 points. You can build even more, accessing the "Tier 2 Floor Area Ratio Bonus," if you set aside at least 20 percent of your units for low-income households. The Tier 2 bonus is the only way you can build to the maximum FAR.

Projects built in the Expo Corridor plan area would accrue a debt of "points" based on their zoning and inclusion of on-site affordable housing. This point debt is paid off by providing local amenities such as a "mobility hub," streetscape investments, childcare centers, and publicly-accessible open space.

As a developer under this system, you know in advance what community benefits you'll be providing. As a city planner, you know you're doing the right thing by capturing the value your rezoning has created and returning it back to the community. It's predictable, at least to some extent, and not entirely dependent on back-room negotiations.

But I have to ask, since I'm sure developers will be wondering when they're trying to determine what they can afford to pay for their land: How much will it actually cost to coordinate with the city and build out an entire streetscape? Or provide a mobility hub as part of your project? What is a mobility hub, anyway? If I build a childcare center, do I also need to fund it in perpetuity? How much does it cost to run a childcare center? Questions abound. There's a certain complexity and uncertainty to this sort of in-kind benefits program, and that may limit the number of people willing to take a risk and build in this area.

And as a community member, what are we doing about larger-scale needs? There's not really a framework for projects of neighborhood-wide significance, like large parks or local transit networks, nor is there much flexibility for trying more innovative approaches to community benefits. (Like a fund for non-profit housing acquisition, for example.)

I think we should be asking for something more simple and flexible. Rather than devising a complex point system and assigning opaque point values to various community priorities, let's just charge a fee. It can be as simple as "for every square foot you build beyond your original zoning, you pay $35." Or $15, or $50, or whatever amount makes sense—figuring out the optimal fee is a job for economists and real estate experts. What really matters is that everyone knows what's expected from them at the outset, and doesn't have to divine it out by expanding their expertise into transportation infrastructure development or childcare or whatever else.

Some nuance: You might have one fee for areas currently zoned for residential, and another, higher fee for parcels where housing isn't currently allowed. As discussed above, changing the zoning designation to allow for housing is particularly valuable, so it might make sense to charge a higher fee in those cases.

We also could consider a lower fee for the first few years—something to encourage the first few developers to take the leap into a market that, while heating up, is still unproven. And it would show everyone else that the fee system works as promised. Fees above a certain floor area ratio (say, 6.0 FAR) might also be lower: Because of building code requirements, the taller you go the more expensive construction of each square foot becomes, and we should try not to discourage developers from building the maximum amount of housing, where possible.

How Much Revenue Value Capture Could Collect

How much value could this create in the long run is very dependent on your assumptions, your fee(s), where development actually takes place, and a host of other factors. Using some extremely back of the envelope estimates, here are some ranges I came up with:

- $1.2 billion, assuming the whole area is only built to an average of 3.0 FAR, fees are quite low ($30 per square foot), and approximately 90,000 new households are built.

- $4.9 billion, assuming the area is built to an average of 6.0 FAR, fees are low ($30/SF), and approximately 210,000 new homes are built.

- $8.1 billion, assuming 6.0 FAR, higher fees ($50/SF), and 210,000 new households.

- $16.2 billion, assuming 10.0 FAR, higher fees ($50/SF), and 375,000 new households.

Again, this is purely for illustrative purposes. The only thing you should take away from the numbers is that a) more housing means more funding for local benefits, and b) the potential revenues run into the billions of dollars.

Allocating the Value Capture Fee

Whatever amount of funds is raised, there needs to be a system for allocating those funds. I don't feel all that strongly how it happens one way or another, but I think we should aspire to a few key principles/categories:

- A large share must be set aside for affordable housing, probably at least 50 percent. Requiring city subsidies of $100,000 to $150,000 per unit, these will absorb a large chunk of the funding. As they should.

- Other essential investments, such as a large park (or parks), transportation infrastructure, and other key priorities should also have a dedicated funding stream of 25 to 30 percent.

- A small amount, 5 to 10 percent, should be set aside specifically for innovative programs that have not been tried in LA, or ideally anywhere else in the country. I'm thinking non-profit acquisition of housing, right of return for displaced residents—stuff like that. Downtown should be a laboratory for experimentation that helps show a better path for the rest of the city.

- Another 10 to 15 percent should reserved for "nice to have" amenities that are left to the community to decide. Whatever that looks like—community centers or school investments, small parks, streetscape improvements, resources for homeless neighbors—would be decided and prioritized through an engaging, extremely public process.

This last idea is one I really love, and I got it from former LA Planning Director Gail Goldberg , who I believe originally learned of it from a similar program in San Diego. The way it was described to me, community members would be deeply engaged in a process that would allow them to choose how they wanted to allocate value capture funds, and to prioritize them in a ranked order. At the end of the process they would have a list of projects, ranked #1 to #25 (or #35, or #99), and as funding came in each project would be implemented and struck off the list.

What I personally loved about this idea is how it makes apparent the connection between new development and community benefits. Every new project would have a value capture number assigned to it—say, $8 million—ten percent of which would go toward a locally-decided investment priority. Not only will that fund 40+ affordable units, improved streets and transportation resources, and other "essentials," it also sends $800,000 directly to whatever is priority #1 on the community's list. In truth this is how most development already works, but it's rarely so clear what the public benefits will be, and it's frequently negotiated on a case-by-case basis rather than decided in advance through a neighborhood-wide process.

Again, the suggestions above are not about presenting the best ideas, but rather framing the issue for further discussion and, hopefully, highlighting the kinds of local investment that become possible with bigger zone changes.

Push-Back from the City

Last month I met with two of the planners in charge of the DTLA 2040 effort to express my concerns with the early proposal and to hear their side of the story. Why not maximize the upzones everywhere possible? And why preserve industrial zoning on such valuable land when it supports so few jobs? Since they know the ins and outs of the community planning process better than I (and probably you), I felt like it was important to get their perspective. I've included a few of our main counter-arguments to the above proposals, along with some of my own commentary.

"Downtown will be zoned to account about 20 percent of citywide growth through 2040. We don't want downtown housing development to absorb all of the city's growth, leaving very little investment in other communities."

I'm writing this one first because it's the one I most strongly disagree with. For one, don't we want to absorb as much of the city's growth as we can? From where I'm standing, downtown is about the only place in the city—the whole region, really—that's relatively welcoming to to change. If we can capture the value inherent in that change and reinvest it in the community, so much the better. We should try to add as much housing here as we possibly can, especially given our central location within the regional Metro rail network. There's no better place to build and grow.

Also, I think the idea that development downtown will preclude development elsewhere is deeply flawed. Perhaps in the short run it's true, but only because we've created such a convoluted development process in LA such that only a few companies are really doing much building. In the long run, though, so long as there is demand there will be people who want to provide the supply. Why artificially constrain the production of a resource—housing—that we so desperately need?

The truth is that we've consistently underestimated the demand in our city, as well as where that demand would manifest. The need to micro-manage the type, quantity, location, style, height, aesthetic, unit size, unit mix, parking, and every other aspect of housing development has a pretty unpleasant track record; we're not omniscient and we've consistently come up short when we've tried to be. I think we'd be much better served leaving our community plans flexible, and allowing the future to take its course more organically.

"Planning for a lot more housing and population means planning for a lot more impacts in the environmental impact report, and putting together EIRs really suck."

Having just completed an EIR for the LA Streetcar, I can confirm that they do indeed suck. A lot. I just talked about how bad we (that is, humans) are at predicting the future, and EIRs are a statewide mandate that we make predictions not only about what will happen in the future, but how it will impact everything from traffic to noise to cultural resources. It's madness.

And in fairness, the push-back isn't only because a bigger EIR is harder to produce, but also because higher populations and housing counts need to be justified. The city needs to be able to answer the question of "why did you choose to study the impacts of 250,000 new residents; where does that number come from?" It's understandable that they'd be concerned, because it was the improper use of population projections (according to the judge, at least) that stopped the Hollywood Community Plan update in its tracks 3 years ago.

Nonetheless, the city can find the justification needed to forecast a large increase in housing and population for downtown. The fact is, just about everything we build fills up—that's how we ended up with a historically low, sub-3 percent rental vacancy rate. If we build the housing, people will live in it, especially if a large share of it is subsidized for low and moderate-income households, and if we can manage to create some middle-market developments that aren't packed with parking and superfluous amenities. And as far as the extra work required to study a more impactful growth alternative, well... ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ...I think that's a sacrifice worth making.

We've asked that City Planning at least study a "high growth" alternative in the EIR, so we will need to organize to make sure they stick to that plan, and that the high growth alternative is actually dramatically more than the 70,000 housing units currently planned, rather than a mild increase that only adds another 20 or 30 thousand extra households.

"If we zone for more development than there's currently a market for, property owners will value their parcels too high and will hold onto them longer, causing us to actually get less new housing overall."

This is an argument I'm sympathetic to, and is actually something I'd considered prior to my meeting with City Planning. Here's the thinking: If you zone land so that a project can be built up to a floor-area ratio of 10:1, but developers only see a market for, say, 5- or 6-to-1, the the property owner will value it as a 10:1 property, but potential buyers will only value it as a 6:1 property. A 10:1 property is worth more than a 6:1 property (because you can build more on it), so the owners will just hold onto it.

Thanks to Proposition 13, long-term property owners are often paying a pittance in property taxes on their underutilized parcels, so they can wait it out. Eventually demand will grow, someone will be willing to build a bigger project, and they'll pay a price that the property owner agrees to. Whether that happens 2 years down the line or 20 is of little import to them.

I can't say that this type of scenario won't come to pass in certain circumstances, but I don't think it will be common. In part this is because, even today, there are plenty of parcels in downtown Los Angeles—especially South Park—that are zoned for up to 13:1 FAR but are only being build to 5 or 6. (To be fair, you do have to pay into the city's Transfer of Floor Area Rights account to build above 6:1.)

Further, parcels that are upzoned will experience an immediate increase in value; if your property just doubled in value, there's relatively little incentive to waiting an indeterminate time to see another 20 or 30 percent increase. If you're actually trying to maximize the return on your investment, you'd rather cash out and put your money in something with a larger upside. If you're not trying to maximize your return, then it doesn't matter what the Planning department does: You're going to sell when you want to, and nothing short of eminent domain can force you to do otherwise.

Last, this is an opportunity to actually see what happens when you zone a neighborhood for considerably more development than you actually expect to see in the next few development cycles. It's something basically no big city has done for decades, because we're all so focused on micromanaging our growth. In theory, with an abundance of land available for development, the value of each individual parcel declines. (Not in absolute terms, but with respect to the cost per square foot of development possible on the property.) If a seller at one site is being unreasonable, you've got a million other options, and competition amongst sellers should drive down land prices. Will this actually happen? I believe so, but I really don't know. I can't think of a better place to test it and find out—the impacts could be transformative for the affordability landscape of LA.

Next Steps

There's a lot going on with this update, and a whole lot at stake, so we need downtown stakeholders to be super engaged with the city's DTLA 2040 team over the next few months. All I've written above is intended as a starting point—albeit a big one—for further discussion about what the community plans should actually look like. As I wrote at the top of this post, I've also put together a much shorter summary of the key issues as I see them, and priorities for action and advocacy. You can find that here.

As with everything I write, critiques and additional input are very welcome. But please, if your comment is critical in nature, pointing out why x, y, or z might not work as I envision, please include your own suggestions for how it could be done better. Naysaying just for naysaying's sake doesn't further the conversation, and a productive, public conversation is what we really need here.

Thank you for reading, and for your involvement on this in the coming months! If you want to get more involved, please shoot me an email through the contact form linked to at the top right of this page! Let's talk!