My first foray into local transportation and placemaking, here I recommend that we close off car access for a section of a popular bar and restaurant corridor in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood.

Read MoreWhat would Seattle look like if Metro fares weren't subsidized?

There are a lot of people out there who consider it a waste to use taxpayer money subsidizing transit fares in urban areas. Obviously I'm not one of them, and my response to those people is usually to note that if all those people drove instead traffic would be (even more) unbearable, pollution and oil dependence would increase, public health and safety would suffer, and more space dedicated to parking in apartment units would increase rents as well.

This usually leads to an argument about how if I want to save the world then it shouldn't be on the car drivers' dollar, to which I respond that the majority of Metro's operating budget comes from sales tax*, which everyone pays (and the lower your income the larger the proportion of your income paid as sales tax), followed by transit fares, then federal and state grants for the capital budget. The total spent on transit by King County Metro is about $1 billion per year. Certainly some money comes directly from those who drive, for example the 2-year $20 vehicle license fee in effect right now that the King County Council approved to mitigate a 17% cut in Metro service last year. There are other things too, higher up in the state budget. But most people who use the bus also own at least one car. So round and round we go, point-counterpoint.

Lately I've been asking the question: what do you propose we do instead? These people seem extremely averse to spending money on mass transit, but especially in light of our growing population and a lack of room for any more roads, I don't hear many alternatives being offered. I'm all for directing more money toward maintenance rather than endlessly expanding our infrastructure (and therefore our maintenance liabilities), but it's obvious that simply maintaining what we've got is a recipe for a steadily worsening transportation system as the population increases. I've yet to get a straight answer from anyone on what they'd actually prefer to see (as opposed to "no more trains!" and "no more war on cars!"), so feel free to let me know in the comments what your vision is for the transportation system if you don't support subsidizing mass transit.

As a thought experiment about public transportation subsidies, here's what I think it would look like if we started demanding that everyone pay the full, unsubsidized cost of their fares:

First off, Metro fares are currently about $2.50 (up a dollar since 2008) in Seattle. We've got a roughly 28% farebox recovery rate, meaning that we recoup 28% of our operating expenses in the form of user fees. If we wanted to increase that to 100% we'd have to charge about $9 per ride and that's making the inane assumption that increasing fares more than threefold will not reduce ridership. So, to get to and from work we're looking at $18, and assuming five work days a week we've got about $360 a month spent just on the work/school commute. Add another ten trips during the month for various errands and we're up to $450.

Many bus riders could afford this, but would they choose to? Given that the vast majority of mass transit users own cars anyway, the question now becomes whether gas + parking (car payment, licensing fees, and insurance already being paid for) adds up to $450 per month, and the answer is almost certainly "no." So everyone who owns a car starts using it for almost all of their trips, even if they used to prefer using the bus or train to get around most of the time.

For those who don't own cars, the decision is a bit more difficult. They have to decide whether the cost of a car payment, licensing fees, insurance, gas, and parking are a better deal than $450 a month in fares. Personally, I owned a 1995 Camry for five years that cost me $5,000 to purchase and about $2,000 in maintenance over it's lifetime, which adds up to about $120 per month for 60 months. Add $50 for liability insurance (if you're over 24 and have a clean driving record, at least), $50 or so for various fees, and $100 for gas (optimistically). We'll ignore parking for now, but I'll get to that later. That adds up to $320 per month, far under the cost of a month of busing and much more convenient, too. So many people who don't currently own cars also start driving them to get around everywhere.

Who's left after that? Basically the very poor, the young, and the very old. In other words, the transit system falls apart due to lack of a constituency and we don't actually have mass transit anymore. Everyone drives everywhere, and those who can't due to age, ability, or income are left to fend for themselves. Even if we limited transit subsidies to just these people, they don't make up a large enough share of the population to constitute a real transit system and many of them already struggle with $2.50 fares, so instead we'd end up with a bunch of incredibly inefficient routes serving a relatively small pool of people. In our quest to end transit subsidies we end up with a system with a farebox recovery rate that is probably closer to 5-10%, subsidized to an even greater degree than before. If efficiency was the goal here we've failed miserably.

And what about all the people already driving as their primary means of transportation? Needless to say, traffic and parking get much worse, particularly downtown where a large proportion of transit trips begin and end. Less of their money is going toward transit projects though, and more toward roads. This does almost nothing to improve traffic in Seattle since there's no room for more roads, but maybe existing roads are kept in a better state of repair. Maybe not though, since all of those cars take a toll on the road, and since congestion has increased everyone is spending more of their time on the pavement. Pollution worsens; people walk around less and sit in traffic more, both of which are bad for physical and mental health; and although the full 1.8 cents of sales tax** that is devoted to transit is no longer needed, those savings are almost certainly eaten away--and then some--by the extra gas wasted sitting in the worsened traffic.

To make matters worse for drivers, with more people now reliant on cars parking in central Seattle will become scarce. This means two things: first, metered street parking rates increase drastically in order to maintain their target of one open space per block; second, as paid parking lots and garages begin to fill up and supply is saturated, demand drives prices for private parking up too. Likewise for parking rates in apartments, driving up effective rents. New apartments and condos built in the city will start including more underground parking (an extremely expensive form of parking infrastructure), adding tens of thousands of dollars to the cost of each unit. This general phenomenon would likely recapitulate itself in every neighborhood center, driving up parking rates not just in downtown, Capitol Hill, and South Lake Union, but Fremont, Ballard, the University District, Wallingford, Queen Anne, Columbia City, Eastlake, etc.

This would be a terrible outcome for drivers, particularly those who preferred to take the bus but can no longer afford it, but it's bad for the economy too. There are already people who avoid traveling to Seattle because of the traffic and lack of cheap parking. (Personally, I hated Seattle before moving here because my only experiences involved driving around in it.) If the buses disappear you can count on that sentiment getting far stronger, and a lot of business that comes in from outside the city will quickly evaporate. That means less business for just about every type of service- or retail-based company in the city, and reduced tax revenue as a result. So all that money we're saving by not sending the entire 1.8 cents of sales tax toward transit? It's at least partially offset by the loss of sales tax revenue from non-Seattleites who now avoid Seattle when they can. That's to say nothing of Seattleites themselves, who are now spending more on gas (or in the case of former busers, transportation in general) and have less money to spend on food, drinks, entertainment, rent, electronics, bicycles, clothing, etc. Once again, this means less revenue for the city, and all those sales tax savings are chipped away even further.

Have I made myself clear? Subsidized public transportation is not a luxury in a large urbanized city: it's a necessity. I made a point of glossing over the moral implications of removing these subsidies not because it's unimportant--it's vitally important--but because the economic argument is sufficient unto itself. By dedicating 19% of our sales tax toward public transportation we ensure that Seattle is able to function as the cultural and economic center of our region. Non-automotive options for getting into, out of, and around the city are essential if we're to retain that position, and our investment in those options more than pays for itself by keeping more spending local, restraining housing costs, and allowing us to remain a viable destination for those who come to our city by car, either by choice or of necessity.

*Fun fact: One-quarter of the sales tax collected for Metro goes toward capital expenses. If the entire 1.8 cent sales tax was directed toward operating expenses, user fees + sales tax revenue would exceed the operating budget.

**The 1.8% sales tax dedicated to transit pays for both King County Metro and Sound Transit.

Increased apartment housing in Seattle likely to stabilize rent prices

It's a common refrain among urbanist types who are savvy to land use issues that increasing the amount of housing in a region can lower rents, or at least slow their rise. The reasoning is straightforward: if you have more demand than supply, prices will increase; if you increase supply to meet or exceed demand, landlords will be forced to compete with one another for renters and prices will decline.

This sounds really great. When you combine it with all the other great things densely-built, transit-oriented development can bring (more walking, bicycling, and transit use; more efficient use of energy and infrastructure; greater diversity of shops, restaurants, and entertainment; more spontaneous interactions with other members of the community; etc.), it sounds even better. But is it true? Do rents really decline just because more units of housing get built? I wanted proof.

After reading this article at the Seattle Times on the boom in apartment building in the Puget Sound region and the effects it may have on rents, I felt like I was on the right track. Unfortunately, the most conclusive statement contained in the article in support of this idea was the following:

[T]he regional apartment-vacancy rate has stopped dropping, both Dupre + Scott and Apartment Insights say, and it should start inching up next year as a bumper crop of new apartment projects comes to market.

That means “rents will basically have to flatten out,” said Mike Scott of Dupre + Scott.

Great news! Not exactly a scientific proof, but I'll take it. Near the end of the article, however:

Even so, 73 percent of landlords responding to that company’s survey said they plan to increase rents over the next six months.

Okay, not so good news. Most of the 35,000 units planned for the next 5 years haven't opened yet though, so maybe landlords are just getting what they can while the gettin's good. Soon enough, the thinking goes, the balance of power is going to tip back toward the renters, and prices will moderate. And a good thing too, since in-city rents for 20+ unit apartments in Seattle have increased by almost 7.5% in the last year (most of that, 6%, in the last 6 months). Has this actually happened? Thankfully, the Times article led me to the answer.

In an article Dupre + Scott Apartment Advisors have produced to accompany the aforementioned survey, they clearly describe some of the trends in the region and break it down into sub-regions with some nice charts. I really encourage you to read the whole thing--it's not too long. But first, and most importantly, I'd like to show you the following two charts from the article:

What I hope you'll appreciate when looking at these charts is their opposing nature. When vacancies are low, rents go up; when vacancies are high, rents go down. That's right, they actually went down! Next time someone tells you it's not possible, and asks you how building new, usually more expensive housing will lower rents, just point them here. It works. And just to be clear, I believe these prices are in nominal terms, not inflation-adjusted, which would explain why prices tend to increase by higher percentages than they decrease. If you provide enough housing to affect vacancies (i.e., enough to meet or exceed demand), prices will go down.

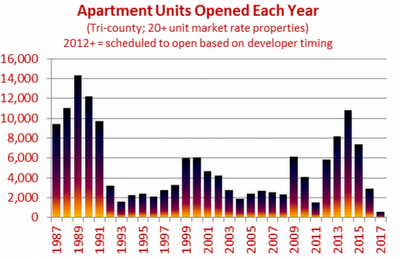

Now I'd like to point out one more chart:

Note how many apartment units were opened in 1999-2002, and then take a look at the vacancy rate for 2001-2005 in the earlier chart. We built a lot of units in that time period, and it seems that this had a significant impact on the market vacancy rate. If you know of something else that accounted for this difference please let me know in comments, but for now I'm going to stick with the sensible conclusion that the supply increased beyond demand and we ended up with a bit of an apartment glut. Prices went down and all was right with the world (for renters, at least). Now look at how many units are planned for 2012-2015. Many more! I suspect that demand for urban living has increased since the early 2000s, but nonetheless this bodes very well for apartment prices in the coming years. And just to drive the point home, note that it took a year or two after the apartments started coming online for prices to start declining. That shouldn't be surprising since the first to open probably only served to soak up the existing unsatisfied demand for living in the regions--it took an excess of supply to actually start bringing prices down.

One more thing to look forward to, renters: besides the large addition of apartments we're experiencing, the real estate market is also improving. That means many people who were forced into renting, or delayed buying a house until they were certain the real estate market had hit rock bottom, are going to start exiting the rental market. So look for this to remove some of your competition as well, driving prices down even further.

So three cheers for providing more housing in Seattle! It's efficient, it's in demand, and it helps keep housing affordable. What's not to like!?

Why would we want to privatize the one profitable Amtrak service?

There's been a lot of news about the GOP's most recent attacks on Amtrak, and my post is largely motivated by this post at Streetsblog, titled "Reminder: Amtrak Subsidies Pale in Comparison to Highway Subsidies". This is an important point and one that most people are probably unaware of, but the quote that really got me in this article was the following:

Amtrak’s subsidies by and large support the long-distance routes, which Congress mandates as a public service. It can’t very well require Amtrak to run these money-losing (but important) long-distance routes and then cut the money to run them – yet that’s what Mica proposes to do. Outsourcing wouldn’t work because no private company would want to take on routes that are proven to lose money. Maybe that’s why Mica’s privatization plan centers on the lucrative Northeast Corridor – the one place Amtrak does make money.

Read the link in that quote too, it's a good one. What interested me about this was why House Transportation Committee Chair John Mica would want to privatize the one Amtrak operation that is running profitably. If the issue is that Amtrak is being run irresponsibly and costing taxpayers a lot of money, shouldn't we want the private sector to take over the lines that are actually losing money? But, as noted above, these subsidies are required because the long-distance routes were formed by mandate of Congress, not because they were expected to be profitable. I'm happy to have a debate about whether these long-distances lines should be operating at all, but that's not what's happening. Instead we're forcing Amtrak to operate unpopular lines and then blaming their inability to turn a profit on incompetence. It's a despicable practice, especially from someone who knows better like Mica.

I was interested in actually finding out where Amtrak is making and losing it's money and I found this FY2012 budget from their site. If you skip to the very last page you can see everything broken down by individual route, and also grouped into three categories: NEC Spine, State Supported Routes, and Long Distance Routes. I've included an image of part of that page below.

As we can clearly see the NEC Spine earns a profit of approximately $230 million a year with 11.2 million riders, almost all of which is thanks to the $50-per-ticket profit on their Acela line, the only high speed rail line in the country. I can understand why Mica wouldn't want to draw attention to that though, given the GOP's visceral opposition to high speed rail and their assertion that it can't be profitable. Looking at State Supported Routes we see a loss of about $160 million a year with 15.4 million riders, although there are a few bright spots (e.g., Washington-Lynchburg, New York-Newport News) where we see decent profits. Then we get to the Dread Long Distance Routes. 4.7 million riders, operating loss of $530 million, a whopping $111.47 loss per rider. Ouch. The best line here loses $60.72 per rider, and the worst, Sunset Limited, loses an astronomical $373.34. So if we take the NEC Spine away from Amtrak and leave it all the losers, how is the taxpayer better off? Without the NEC, we'd have paid out $690 million instead of $466 million.

If anything, this sounds like a great reason to invest more in the NEC corridor. It's the only transportation mode that's making any money, after all. Not only would it improve the quality of service there, getting people between D.C., New York, Philadelphia, and Boston faster and more comfortably, it'd also attract more riders away from money-losing aviation (government subsidy of $4.28 per ticket), intercity buses ($0.10), and cars (unknown, but certainly subsidized). That sounds like a pretty smart move for anyone who cares about saving taxpayers money, and it has the added benefit of being more environmentally friendly and reducing road and air congestion.

As it stands, Mica seems more interested in privatizing profits and socializing losses than actually improving Amtrak operations.

With bike share coming, can single-stop buses become viable?

As an infrequent--but aspiring--bicycle commuter living at the top of a hill (Capitol Hill) and working at the bottom of one (University of Washington), I've long dreamed of a way to bike to work without having to deal with the difficult, sweaty ride back home. Call me lazy if you like, or try to convince me that if I just got used to it I wouldn't mind so much, but the fact is that if I could ride my bike to work without having to deal with the hassle of taking it back on the bus I'd be much more likely to ride regularly. And I sincerely doubt that I'm alone.

About a year ago I was thinking of possible solutions to this and came up with the idea for a "Bike Bus" (honk honk), a vehicle operated either privately or publicly that could carry both people and their bikes from low points in the city to the high ones (e.g., UW to 15th & John at Capitol Hill and 65th and Roosevelt in Ravenna, or Pioneer Square to Queen Anne and First Hill), allowing them to easily ride on a flat or level path to their destinations once they got off the bus. This Bike Bus would have the added benefit of being much faster than the regular bus: it would only stop at the low point for pickup and the high point for drop-off, with two, one, or even zero stops in between. We could ride our bikes to work or school, get home without being drenched in sweat, and get a faster trip home than usual to boot! There'd also probably be quite a few bus riders who found this convenient, like a super-express version of their normal bus commute. Win-win-win-win!

This idea had some flaws. Operating privately would be incredibly difficult without some kind of agreement with Metro, for one, due to so many people (myself included) expecting their ORCA card to cover all transportation expenses. I already pay a monthly fee for the pass, why would I want to pay extra money just for this little convenience? There's also the logistical issue of how you actually carry so many bikes from one place to another. Do you get something like what's currently found on the front of buses, but bigger and pulled behind on wheels instead? A trailer with places to secure it inside? Find a way to get all the bikes inside the bus? None of these sound like very good ideas to me. In fact, Jarrett Walker at Human Transit just wrote an article about the geometric impossibility of fitting more than a few bikes on a bus, among other things.

But the biggest problem by far is frequency. The locations where a Bike Bus would be useful already have 10-minute or less headways during peak hours, and the people who use those intermediate stops on the regular bus wouldn't be too happy to increase their headways to squeeze in some Bike Buses. After all, the bikers can still use any bus they want, but people who live somewhere in between are still stuck with the regular bus. And without a frequency approaching that of existing service (it could presumably be a little less frequent since the trip itself is faster), this simply won't be appealing to anyone. I couldn't come up with a workable solution to this problem, and combined with the other issues I just decided to drop the idea altogether. Oh well.

Enter bikeshare. Suddenly we don't need to worry about carrying everyone's bikes from point A to point B because there are already plenty stored at both. Since Puget Sound Bike Share is a non-profit we can hope that they'll be coordinating with KC Metro, and I'd be ecstatic if they integrated ORCA cards into the payment system. I know some of the guys at Seattle Transit Blog are big proponents of more and better distribution of ORCA cards, and bike share stations seem like a perfect place to dispense them from.

Frequency is still the big problem, but with bike share I think we get one step closer to closing the gap on this. Specifically, one complication with bike share is that inputs and outputs at specific docking stations are never exactly the same, so the operator has to employ people to truck bikes from overburdened stations to those with openings. Why not do double duty and pick up some people while you're at it? The vehicle could be a large-ish shuttle with a trailer behind for storing bikes, and once the driver has picked up the bikes they need from the area they could pick up passengers from a designated area and whisk them off to their destination. On the way back down the hill the driver can drop off the bikes where they're needed, then repeat. Frankly I have no idea how many employees a bike share operator would need to perform this function in a system of 2,200 bikes (the amount planned after all phases have been implemented), but it'd probably be several at least, and with a subsidy by KC Metro that could be increased since the passenger side of their activities would certainly cut into their bike relocation time.

I realize this is kind of an off-the-wall idea and far from completely worked out, but I think it's a good starting point for thinking about how we can a) encourage more people to use transit and get around on their own two feet (or wheels) more; and b) how we can make the best use of bike share when it comes. Much has already been said about how our infrastructure needs to improve for bike share to be safe and successful, but maybe we should also consider what we can do on the operational side to promote synergy between our transit system and bike share. I encourage any ideas related to the "Bike Bus" concept as well as any unrelated thoughts about how we might improve transit operation once bike share hits the street.

Texas caters to private toll road operators at the expense of the public

Texas recently approved a speed limit of 85 miles per hour for a new 41-mile segment of a privately operated toll road, and is getting a big payout in return for the favor. That payment amounts to a cool $100 million dollars, $33 million more than they'd have gotten for setting a speed limit of 80 mph.

There's a lot not to like about this deal, and people are rightly questioning how this is going to affect safety on this stretch of freeway, part of State Highway 130. Specifically, the Wall Street Journal article refers to a 2009 report in the American Journal of Public Health, which "found that higher speed limits adopted by states in the wake of the 1995 repeal of federal speed-limit controls had led to a 3.2% increase in road fatalities, or an estimated 12,500 more deaths from 1995 to 2005." As one would expect, increased speeds lead to more severe injuries, and it's not unreasonable to imagine it might also lead to an increased number of accidents in absolute terms due to the added challenge of driving at higher speeds--especially in adverse conditions like inclement weather or in response to erratic drivers.

The safety issues associated with this speed are undoubtedly the most consequential and immediate problem with this change. But there's another problem here that is really troubling, and that's the reduction of the speed limit of an adjacent, parallel freeway. This parallel freeway, of course, does not have a toll; so, as long as congestion isn't too awful or people don't feel they can afford the toll road they'll go with the free option. That could be a problem for the private toll road operators, so the very same year (coincidentally I'm sure) we see a reduction of the speed limit for their competition, making the free road an even less attractive option.

This is where I really begin to question the commitment of the Texas Transportation Commission--and perhaps the Texas government more broadly--to the public good. Government builds roads to facilitate movement of people and goods which is obviously vital to a society and to an economy. To me and most other people there are endless examples of how government does a poor job of allocating these transportation resources effectively, but that's really a value judgment based on your feelings regarding choice, pollution, personal freedom, economics, sustainability, safety, and so on. Putting that aside, once the infrastructure investment has been made we should be using it rationally and efficiently, and that is absolutely not happening here.

In effect, the Texas government is stacking the deck in favor of these private operators at the expense of the rest of the motoring public. When we look at a toll road competing with a free road we can expect less traffic on the former, so it already wins on congestion, and even before the speed reduction it wins on speed. But just for the sake of throwing a little extra money into the coffers of the guys running the new freeway (and you can bet it's not being distributed among too many people), Texas is willing to sacrifice the safety and money of its citizens and squander the investment already made in the previous road by forcing it to be used sub-optimally. Texas actually gets a cut of the tolls as well, not just the $100 million, but if it's really all about more money for the state why not just put a small toll on the old road and leave the speed as it was before? At least then people aren't forced to make the disturbing choice of either a) congestion and/or low speeds, but free, or b) open roads with increased cost and an increased chance of death. For such a free-market state, you'd think they'd want to go with the more "everyone pays their own fair share" method of raising funds rather than this backdoor money-grab.

Most importantly, private competition should never come at the expense of the level of service offered by the government.

If we allowed multiple utility companies in a given region would the private competitor be allowed to pay off the government to limit the number of outlets at customers' homes? Do we start limiting the amount of medical care Medicare patients receive just because they've reached some arbitrary cap, and then force them to take their chances on the private market? (Oh, wait...)

I can't say for sure whether privately administered roads is something that should even exist or not, but when private companies get into the business of competing with basic government services there need to be serious safeguards put in place. This clearly hasn't happened in the case of Texas transportation, and it sets a very serious precedent.

L.A. County hoping to speed up transit infrastructure construction

An Expo Line test train rests at the La Cienega station, with the downtown L.A. skyline in the distance. Photo by Steve Hymon/Metro via Wikipedia.

L.A. County residents are preparing to vote on a measure approved recently by the county, state legislature, and governor to extend the most recent transportation-dedicated 1/2 cent sales tax measure for an additional thirty years beyond it's current expiration date, in 2039, all the way out to 2069. Rather than adding any new taxes, the intent is to expedite the construction of currently planned transportation infrastructure by bonding against revenue to be collected in the future - in this case, the pretty distant future. Read more about what L.A. County has accomplished so far in Yonah Freemark's article, linked above.

If this measure fails some of the major rail projects in the region will require decades to complete rather than years, but Freemark brings up some valid objections to this plan (although he seems generally supportive of it on the merits). I'll address these in the order in which they appear, starting with the question of what happens if in 2040 L.A. County residents decide they're actually not happy with the infrastructure that's been built.

Firstly, based on the trajectory of urban areas over the past few decades it seems very likely that people will appreciate these transit investments and they'll get plenty of use. As cities have grown up, particularly in their central/downtown regions, transit has become a more and more integral element of transportation and there's no sign of this changing. Even with the advent of driverless cars there's no changing the fact that cars take up a lot of space, and to accommodate the number of people who want to live and work in cities we need a way to move more people using roughly the same amount of space. That's transit, and barring some incredible and unforeseen innovation in moving people from place to place, it's going to remain transit. The only really plausible reason that a region that once wanted better transit might change its mind seems to be that it suddenly started becoming less dense and less populated, which I doubt any part of L.A. County is planning for. Building out this infrastructure (and building it quickly) actually speeds up this densification and development process, so the chances of this happening anywhere in L.A. become even less likely as the projects move forward. And let's not forget that L.A. residents have already voted to increase their sales tax by 1/2 cent three times in the past 32 years, most recently just four years ago, so they seem to approve of what's been built so far.

He also notes that 'The referendum would extend the tax “for another 30 years or until voters decide to end it.”' So, what if voters decide to end this tax? Well, I don't think it really matters. The same thing happens as if any other source of revenue suddenly disappears: you find another way to pay for it or you make cuts elsewhere. If it's a matter of finding another way to pay for it this might actually be a good thing, given that sales taxes are one of the most regressive ways for a government to raise revenue. If it's a matter of making cuts then you find a way to make them, but I think this is all semantics anyway. The odds of this being overturned in the future seem exceedingly low. For one, although sales tax measures for transportation investment don't always pass, I'm not sure there's any precedent for one actually being repealed after being approved by voters (especially by a 2/3 vote). If you know of one I'd like to hear about it, but I suspect it's extremely uncommon if it's happened at all.

This also fails to recognize the increased revenues that always accompany major transportation projects - between the increased values of properties near rail lines and the billions of dollars of new development that's likely to accompany it, this isn't just an extra cost for the county and it's residents - it's also a way to bring in more tax-paying residents, more businesses, and more investment. And by expediting these projects all of the attendant benefits accrue to to the county earlier (to say nothing of decreasing the amount of time that construction disrupts business and mobility in the area). You can finish the subway in 2020, or you can finish it in 2036 and miss out on those 16 years of increased revenue.

The measure also "does not specifically guarantee that the projects promised back in 2008 will actually be delivered," but seeing this as a negative is an implicit expectation for incompetence on the part of the county's leaders. As he notes, so far L.A. has done a good job of staying roughly on time and on budget, and just like planning for a city to decline in population even though you don't want it to, this would be a very strange way to handle future planning. If said leaders are being poor financial stewards of the county's major projects, we have elections to replace them with people who will (hopefully) get things right. Failsafes and backup plans are completely justified, but everything has risks and a no vote based on that fact is a recipe for stagnation and decline. This may also be viewed as a sign of adaptability and a retort to those who worry what we'll think of these projects in thirty years - it provides room to modify and optimize plans as circumstances dictate.

As Freemark notes, if L.A. wants to get these projects done anytime soon they don't have many other options, particularly with declining assistance from the federal government. And given the current state of the labor market and the reduced cost of contracting in this depressed economy there's no better time than now.

Texas to incentivize driving for decorated veterans

Starting in 2013, Texas is giving disabled and decorated veterans free access to most of the state-run toll roads

as a way to show appreciation for their service. Maybe there's some nice metaphor in there about vets who've lost some personal mobility due to injuries acquired on the job and the Texas DOT helping make up some of the loss for them, but as a policy this plan falls flat on its face.

The article doesn't discuss what this means for veterans who are unable to drive due to their injuries, for whom this proposal seems kind of like a slap in the face, but that's far from the worst thing happening here.

Toll roads usually exist to pay for transportation infrastructure and maintenance so by neglecting to collect this money they're necessarily choosing to spend money from elsewhere (maybe transportation-dedicated, maybe general fund) to make up the deficit. In other words, Texas has decided that out of all the possible ways you could spend one million dollars a year to benefit veterans, this is the best choice. Let me just say that I think it's perfectly acceptable (and actually admirable) to provide special services or discounts to our veterans, particularly those who have been permanently harmed during the course of their duty. But is this really the best we can do? On the scale of really horrible to really wonderful things to do for our veterans, is this even "better than nothing"?

It's established that tolls will reduce traffic volumes on a corridor. Some of this is because the trip isn't that important so they just don't take it, some of it is people taking alternate routes, some of it will be people carpooling or using transit instead, and if it's a variable toll some of it will be people traveling at non-peak hours in order to save some money. There are issues with the variable toll price in that you've got a group of people who are not subject to the market forces at work and therefore will not travel at optimal times, negatively impacting traffic overall, but after a cursory glance at TDOT tolls they don't appear to have different tolls at different times of day. It's a pretty small group of people anyway, so it wouldn't be a huge problem in this case, but could in other circumstances.

The real issue here is why is Texas incentivizing driving for this group at all? Or for any group for that matter? This is just an educated guess, but I doubt it's written into the TDOT mission statement that one of their goals is to increase the use of regional highways by single occupancy vehicles. If you're going to take a million dollars out of the state's budget to help out veterans, why not just give them a check every year and let them decide how to spend it? There's only an estimated 7,360 eligible vets in the area, so that works out to about $136 per person. I'd be pretty excited to receive a $136 check from the state, and I can tell you that I probably wouldn't spend it joyriding around the freeway in my car. Or if you wanted to make things more complicated you could probably get some good value in jobs training programs, housing aid for lower-income vets, medical care, etc. If you wanted to keep it transportation-based, why not give them a benefit that's actually good for their health like a free transit pass, a bike, or a good pair of walking shoes?

Giving people more reasons to sit in their car is completely against their interests, and it's all the worse that we're doing this for (or to) the members of our community that have sacrificed the most for us. Longer commutes are correlated with obesity and more specifically it's been shown that sitting all the time is bad for your health. And lets not forget that tolls are far from the only cost associated with driving: encouraging more driving means encouraging more money spent on gas and car maintenance, among other things. That might be good for Texas oil interests, but it's not good for veterans or anyone else.