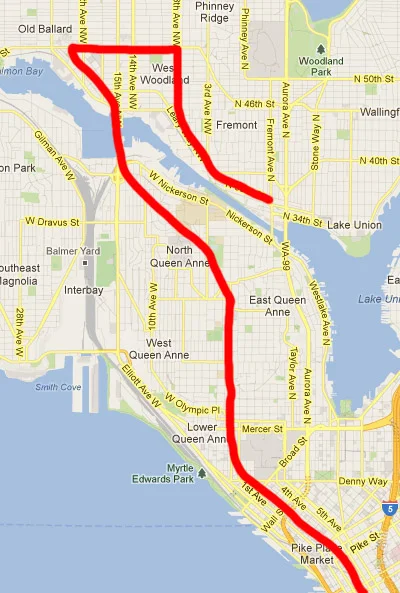

South Lake Union concept art, from Studio 216.

As a part of the ongoing redevelopment wars going on in the South Lake Union neighorhood, Publicola recently wrote about yet another half-measure approved by the Seattle City Council, this time in regard to the fees developers pay for additional density. Publicola reports:

The city council, meeting as the special committee on South Lake Union, unanimously adopted a compromise incentive zoning plan for South Lake Union (for our extensive previous coverage, start here) this afternoon that would allow developers to build taller, denser buildings in the growing neighborhood in exchange for new, on-site affordable housing or payments into an affordable housing fund.

The proposal the council committee adopted is most similar to a compromise proposed by council member Mike O'Brien that will require developers to pay $21.68 into an affordable housing and child care fund for every additional square foot of density above what's allowed under existing zoning rules. The proposal would increase the requirement, known as a "fee in lieu" of building affordable housing, annually according to the rate of inflation.

The mayor's proposal called for a fee of just $15.15 per additional square foot of density, a level that appeared much too low, given that "developers who've taken advantage of existing incentive zoning rules in South Lake Union and downtown have universally chosen to pay into the fund instead of building actual affordable housing." If the goal of the program is to incentivize construction of affordable housing, the $15.15 per square foot cost was clearly failing on that measure.

Councilmember Nick Licata proposed that we increase that fee to $96 per square foot, a level that effectively ensures any additional density results not in fees but in affordable, on-site apartments. This proposal was shot down, apparently because it was unrealistic that any developer would be willing to pay such a large amount.

My question is, why is that a problem? If the goal is for private developers to build more affordable housing--and they can build it more cheaply than the city, so it should be--it shouldn't matter if they always opt to build rather than pay the "fee in lieu". Assuming building affordable units in exchange additional building height/density is a profitable proposition for developers, it doesn't matter what the fee in lieu is set at. The fee should be set at a level that is less appealing than providing on-site affordable housing. It probably doesn't have to be $96 per square foot, but $21.68 is probably still far too low. And if developers are opting to not build additional density at all, then the incentive program has much more fundamental flaws than the fee in lieu amount.

This all goes back to the question of how committed the city council and mayor really are to providing affordable housing in Seattle. Last month the council passed up more than $10 million in funds for affordable housing in order to arbitrarily limit building heights in SLU to 160 feet, which will have the dual negative effects of reducing the number of affordable units and limiting the total available supply of housing in a fast-growing and highly desirable neighborhood. Now, working within the framework of those 160 foot heights, the council seems to have compromised with themselves yet again, to the benefit of no one, for weak-hearted incentive zoning rules as well.